In my post “How to Educate a Frog” (May 25), I argued that AI poems are just what humanly written poems would have been like if professors of literature had been right when they taught generations of students that literary works are nothing but mere texts—words on a page which can be interpreted without reference to an author’s intentions. If I am correct, AI poems can generate texts that can satisfy all the formal requirements of poetry, but because there is no worldly context for their performance, no actual speaker, and no particular audience, there can be no power of suggestion beyond what is actually said. Without the creative mind there are no ulterior motives, no ironies or unspoken subtexts to detect. So if you had poetry classes in college where you were told not to think about what the authors could have meant, either they were extremely boring classes or your professors couldn’t stick to their own rules. Probably the latter.

But isn’t it possible to instruct the machine to build unstated contents into its creations? To explore this question, I asked ChatGPT to rewrite “How to Educate a Frog” in such a way as to make it more ambiguous.1 As if to signal its unwillingness to confuse, the machine added a warning label, “Ambiguous Version,” to the title of its new version.

How to Educate a Frog (Ambiguous Version) I. Pondside Theories Begin by the water, where reeds murmur and lily pads drift. Lessons wait in the shimmer, but what they teach— well, that depends on who’s asking. II. Reflection Follow the dragonfly, its darting path may mean something, or nothing at all. Notice the beetle’s quiet persistence, the tadpole’s shifting form— but ask yourself, what truly changes? III. Stillness Sit, if you must. Watch the heron— is it patience, or simply hunger? Perhaps the waiting is the wisdom, or perhaps the wisdom never comes. IV. Language Listen to the croaks, as though words hide in the noise. Speak back if you like— though who’s to say if anything’s understood? The ripples don’t explain themselves. V. Edges The boundary shimmers, but is it really there? Ponder the shore, and what lies beyond— or stay. Dreams may or may not come to those who leap.

The machine claims, in an unprompted postscript, that “This version introduces uncertainty into each section, leaving more space for interpretation without clear outcomes or lessons.” The “Ambiguous Version” does indeed have some ambiguity added, but not to the poem itself. Instead, ambiguity has become part of the poem’s subject. It is the student-frog who has been given more space for interpretation, not the reader. “The ripples” may not “explain themselves,” but the poem remains perfectly transparent. And while being transparent, it is much worse as a poem than the original, which at least takes a definite stance. No more “dragonfly, irridescent teacher.”

Next I tried asking the machine to rewrite the poem “in such a way that the message is inadequately expressed.” This seemed to improve it a little by making the action amusingly generic. “Frog stuff happens near water,” it begins, and “Beetles exist and do beetle things.” Sadly, the frog’s “moist dialect” has lost its clarity, with “no translations provided./The water’s involved. Splash if you feel like it.” The ending is “kind of unclear.”

Once again the machine provided an explanation: “This version leaves the ideas unformed, glossing over key concepts and missing the essence of what’s meant to be conveyed, creating a sense of vagueness and incompleteness.” But this vagueness and incompleteness are precisely and completely achieved. Bad human poems aren’t like this. They try to express something well but fail. Here, though, the vagueness and incompleteness are fully explicit in the poem, which still leaves no room for interpretation.

The New Critics who promoted the slogan “Intentional Fallacy” in the 1940s valued irony as the essence of literary language, but what they meant by irony was really the kind of multiply ambiguous statements that, in their view, made literary language different from the languages of science and everyday life. They wanted to enhance the ambiguity of language by cutting out the author. But writing poems with ChatGPT suggests that, without a human author, sentences lose their potential to carry more than one straightforwardly conventional meaning.

I asked the feed for yet another rewrite, which turned out to be not so much about frogs as “the existential crisis of water.” This time I’ll drop the warning label and let you guess what the instruction was based on section one, “Wet Circles and Floating Objects.” Take the poem’s advice—“Expect nothing, but expect it intensely.”

Start near, or maybe inside, the wobbly stuff. There are... green things? They sway like thinking, but not. Bubbles appear, or don’t, while ants play chess with shadows. Ripples speak, but nobody’s sure what they’re saying.

This is the beginning of the “Incomprehensibly Bad Version.” According to the machine’s own account, it “completely muddles the original meaning, making the content almost entirely incoherent and disconnected from any clear message or purpose.” The “existential crisis” in this version is indeed quite serious, and there are some notes of true mystery—“wobbly stuff,” “green things”—but the poem quickly falls back into the machine’s typically whimsical poetic logic, with irrelevant ants that “play chess with shadows” and “cows that ride bicycles into space.” The main ingredient that the prompt seems to have added is a certain cynicism, which inspired me to ask for an explicitly cynical version. Here’s how it starts.

How to Educate a Frog (Cynical Version) I. Pondside Disillusionment Start at the water, if you must. Cattails sway, lily pads float— none of it means anything, but sure, pretend it’s profound. Insects? Algae? They do their thing, but don’t expect a life lesson from slime.

Obviously the cynical version has a certain aphoristic force. Predictably, it finds no enchantment in what it calls “frog talk.”

Learn the language of croaks? Sure, because nothing says “communication” like mindless noise. Talk to the reeds, to the water— but don’t expect them to answer, because, surprise, they’re indifferent.

A clear rebuke to romanticism, the poem ends in batrachian despair.

You’re a frog, stuck in a pond. Dream of oceans if you like, but deep down, you know you’ll never leave the muck.

Here we are getting to the point where the AI Frankenstein threatens to come alive. We have given it a distinctive tone by asking it to mimic a human attitude—not a typically poetic one—and asking it to generate a perspective on an example of something (nature poetry) which the machine itself has created. It is still the case that nothing is left unsaid here, but what is said has acquired enough layers to make the authorless words seem meant. This may be because, with this sequence of experiments, we are beginning to generate the sense of a context, in which the cynical version contrasts with the initial one. Still, no one is actually taking up this cynical stance toward frog-speech or nature poetry in general. What we are getting is an extract from the World Wide Word-Stream.

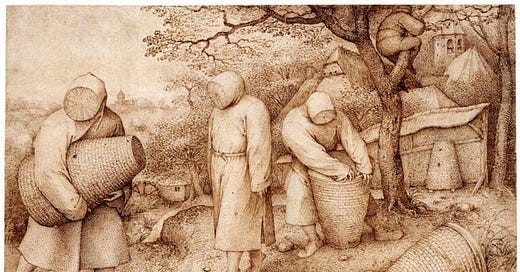

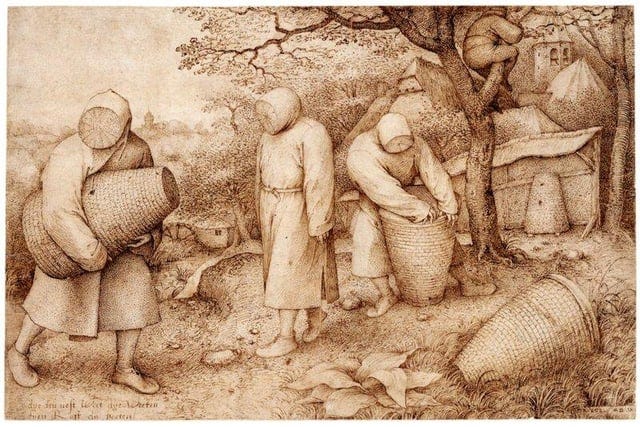

None of the Chat poems I have generated get beyond the charms of a cleverly executed formal exercise, but here is one with an element that took me by surprise. The surprise comes in the final line, which is, of course, the best place for a surprise. Again I provided the title as a prompt. (By the way, the poem taught me that propolis, also known as “bee glue,” is a resinous substance gathered by bees and used for various purposes in the hive.)

The Rudiments of Beekeeping Begin with the hive, box of intricacies, a labyrinth for queens and workers, drones and comb. Each cell a receptacle of sweetness, each corridor a path to the complex heart. Don the veil, a shroud against stinging, your face behind mesh, a soft-focus world viewed through safety. Gloves up to the elbow, armor for the hands that reach into the humming. The smoker waits, a tool of persuasion, its puffs coaxing bees to drowsy calm. Ignite the fire, tamp it down, smoke wafting like slow-moving fog. Frame by frame, lift the architecture of bees. See them cluster, watch them dance, a ballet of information— the location of nectar, of water. Brood pattern, honey stores, markers of a thriving community, or signals of disease, of parasites, of a queen gone rogue. Taste the honey, each flavor a map of blooms, of seasons. It is the distillation of time and place, the work of countless flights to daisy, to clover, to lavender. Close the hive, leave an offering— a bowl of water, a sprig of flowers. Withdraw, but carry the hum, the scent of beeswax and propolis, the essence of life’s rudiments made manifest in the Keeper’s craft.

Now it doesn’t take a lot of experience with reading poetry to see that the capitalizing of the word “Keeper” enlarges its meaning. Who could this Keeper-with-a-capital-K be other than God? Capitalizing most words in most contexts, of course, would not promote their meaning in this way, and there is nothing particularly spiritual or supernatural about the word keeper. But a keeper in charge of a hive has a potentially godlike post of supervision, and this likeness between keepers and God allows the machine to exploit an extremely uncommon typographical resource, one that cannot be very frequent in its database even among the training texts marked as poetry. It is very spooky.

Unfortunately—or maybe I should say fortunately—going back through the poem with the new identity of the Keeper in mind doesn’t seem to add much. The poem is a series of commands for its readers prompting them to rehearse in imagination the operations of the “Keeper’s craft,” but it is in the third person and the Keeper appears only at the end. The “architecture of bees” is mentioned but the overall design of the hive isn’t stressed. There is no issue of theodicy. God’s bee-keeping purpose will have to wait for later updates of AI.

Here’s the original version.

How to Educate a Frog

I. Pond Life

Begin at the water’s edge,

where cattails sway and lily pads offer platforms for discourse.

Here, in this aquatic classroom,

observe the curriculum of insects and algae—

lessons not in books, but in ripples and croaks.

II. Observation

Watch the dragonfly, iridescent teacher,

its flight a lecture on aerodynamics.

Note the beetle, a study in armor and utility,

and consider the tadpole—your own youthful reflection—

its metamorphosis an education in becoming.

III. The Art of Waiting

Sit still, eyes like twin moons

open to the sky and the canopy above.

Learn patience from the heron,

its unwavering focus a testament to intention.

Remember: wisdom often comes

to those who wait.

IV. Communication

Master the language of croaks and chirps,

each utterance a word in a moist dialect.

Speak not just to your kin but to reeds and fish,

to the very water that sustains you.

Expand your lexicon with ripples and splashes—

the syntax of survival.

V. The Limits of the Pond

Contemplate the pond’s edge, that finite boundary,

and what lies beyond—fields, roads, unimaginable terrains.

While you are a creature of water and shade,

let curiosity tempt you toward the unknown.

After all, even a frog can dream of oceans.

Maybe the one bright spot at the moment is that it was my prompt that provided the humorous scenario. When I asked the machine to come up with its own topic, it wasn’t as successful.

The frightening thing is that these variations would all probably earn an A for any high school English student. There was an article online today about Gen Z not reading to their young children because it's "boring." I worry that a decline in literary interest and the ease of faking it will have real consequences for younger generations. Though I'd probably give an A to some kid who wrote, “Frog stuff happens near water,” the frog’s “moist dialect,” and "Splash if you feel like it," just because it made me laugh. Maybe I'm part of the problem after all.